- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

September 2023 saw the first fruits of a major new cross-industry project to acknowledge the contribution of an underrepresented group in maritime. With Rewriting Women into Maritime History putting on a special exhibition for London International Shipping Week, Sarah Robinson explains how Nautilus has been involved

When we think of women in the 1970s workplace, we might envisage putupon secretaries with lecherous male bosses, or female factory workers whose skills with a sewing machine were less valued than those of male welders.

Yet, for the first time in history, employment law was starting to be on women's side. In the UK, the Equal Pay Act 1970 had prohibited any less favourable treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment.

Even in the notoriously traditional Merchant Navy, we started to see young women choosing to train as deck, engineer and radio officers – attending nautical colleges alongside young men, getting jobs at sea on the same terms as their male counterparts, and joining the same maritime trade unions.

To contribute to the project Rewriting Women into Maritime History, we decided to take a look at officer pioneers of the 1970s. Working with maritime historian Dr Jo Stanley, we identified three examples of women who were among the first female members of our predecessor unions MNAOA (Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association) and REOU (Radio and Electronic Officers' Union).

On this page you will find the stories of a deck officer, an engineer officer and a radio officer who all started out in the 1970s. In our interviews with them, Linda Craig Forbes, Marion Pettigrew and Rose King each had something to say which was both highly individual and representative of other women seafarers of the era.

She Sees exhibition and Rewriting Women website

Our three chosen 1970s Union members were featured in the: She Sees exhibition at the International Maritime Organization headquarters in London, organised by the Rewriting Women initiative as part of London International Shipping Week on 11-15 September 2023.

And there was an additional reason to visit the IMO on those dates. As well as telling the stories of maritime women from history, the She Sees exhibition shone a spotlight on the female seafarers of today – including numerous Nautilus members who had come forward to be photographed and interviewed.

For those unable to visit the exhibition, the good news is that all the contributions to the Rewriting Women project are now online on a website hosted by the project coordinator Lloyd's Register Foundation. There you will find the stories of women from a range of maritime sectors which were uncovered when the Rewriting Women partner organisations delved into their archives.

Rewriting Women goes international

The She Sees exhibition and website represent the culmination of the first phase of Rewriting Women into Maritime History. This focused on highlighting the activities undertaken by women in shipping over the past few centuries in the UK and Ireland.

Now that these stories are in the public domain, the project will spread internationally from 2024.

As an international organisation itself, Nautilus is poised to find out the stories of women members past and present in all its branches next year. We will focus on the Netherlands and Switzerland, but there could also be an opportunity to tell more women's stories from the UK and Ireland.

- If you are a woman member of Nautilus International, please keep an eye out for any emails or Telegraph articles inviting you to come forward for the next phase of the Rewriting Women project, or you can express your interest by emailing telegraph@nautilusint.org

LINDA CRAIG FORBES – DECK OFFICER

For the first of our 'officer pioneers of the 1970s', we were very fortunate that past Union member Linda Craig Forbes was able to share her maritime experiences with us in the last months of her life. Dr Jo Stanley tells the story of an exceptional seafarer

Linda Craig Forbes was Scotland's first woman deck officer, though not by design. 'It never crossed my mind that I'd be a pioneering woman on ships,' she said. But when she saw an advert for sponsored deck cadetships, it didn't say 'boys only', so she sent in an application and got an interview.

Born in 1957 in Inverness, Linda had done well at school and initially hoped to become a veterinary surgeon, but there wasn't the money for her to train, and she needed to find a career with funding, so a Merchant Navy cadetship fitted the bill.

She didn't know of any seafarers in her family circle, but there were two adventurous female role models. An aunt had been a rare naval nursing sister in the Kenya Emergency (1952-60) and a greataunt had 'gone up the Amazon in her 80s.'

As well as inheriting this family spirit, Linda was equipped for the Merchant Navy with determination, experience in handling two younger brothers, and a practical mindset. 'I was never a girlie girl,' she noted. 'My standard rig was casual, with trousers'.

College and sea training

Linda's introduction to seafaring was at Glasgow College of Nautical Studies, where she was the only woman on her deck officer course and in the attached Sauciehall Street hostel. She didn't recall any problems with her fellow trainees, but she had mixed feelings about being celebrated in newspapers as the 'first lady cadet in Scotland'.

Linda's first trip was with Scottish Ship Management Ltd on the new 14,651-ton grt Cape Grenville, which carried sand from Western Australia to Honolulu. Cadets were always treated as the lowest form of marine life and allocated the jobs no one else wanted to do. However, Linda felt 'I didn't get it any worse because I was a girl.'

She was happy to work on cargo vessels rather than passenger ships, not least because you could reach a higher rank more quickly. Usually the only woman onboard, she was joined occasionally by officers' wives.

Colleagues tended to be avuncular and helpful, especially if they were older men with daughters: 'If I was getting a rough deal at the hands of the stevedores, some of the crew would intervene to support me.'

Rising through the ranks

On qualifying as an officer of the watch, Linda served on Stephenson Clarke Shipping coastal bulk carriers, carrying coal to London docks, and then worked for Turnbull Scott, Dart (Canada) containers in the North Atlantic.

A career on all kinds of cargo vessels later saw her rise to second mate and chief mate. She funded her own training for the higher tickets. Her trade union membership card has gone by the wayside, but like all British deck officers of the time, she would have been a member of the Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association (MNAOA) – a predecessor of today's maritime union Nautilus International.

Challenges in the Middle East

Linda rarely had any problems getting crew to obey her orders, but her sea career ended partly because of gender. In the Persian/ Arabian Gulf of the early 1980s, Linda found – like others before her – that the local men in the region often had trouble obeying women's orders, which meant that loading and unloading was expensively held up.

Unfortunately, shipping companies saw that the fastest solution was to dispense with women deck officers rather than trying to change Arab men's mindsets.

And the general recession didn't help.'I think being female counted against me,' Linda reflected. Seemingly, shipping companies saw women as more expendable than men in times of trouble.

A productive life ashore

After leaving the sea in July 1981, Linda's careers included publishing and then renewables. She became procurement director for Scholastic, with a multimillion pound budget. She later held directorships of Caspium Ltd, Renewable Energy, Shelter & Environment Training Ltd, and Energency Ltd.

On top of work, she gained a degree in engineering from the Open University, then two master's degrees in engineering and architecture.

In Orkney, she worked with the European Marine Energy Centre on marine renewables. She helped o set up Stromness Community Garden and was a valued board member of Orkney Housing Association.

She was also a Passivhaus designer. A member of the Women's Equality Party, she set up the Southport and West Lancashire group of the Fawcett Society in 2021. Her interests included bird watching, arts and crafts and genealogy, and she discovered to her surprise that one of her greatgrandfathers had been a seafarer.

Strong to the end

Linda died aged 65 in December 2022, of cancer, in Southport's Queenscourt Hospice. She was annoyed that she would not reach 66 to be entitled to the state pension she had paid into for 49 years! Respecting her wishes, there was a private cremation. She left behind a partner, Timothy, and her memorabilia is being donated to appropriate archives.

MARION PETTIGREW – ENGINEER OFFICER

Our engineer officer pioneer Marion Pettigrew shows how drive and determination can get you a long way in a maritime career. Sarah Robinson meets a woman who would never take no for an answer

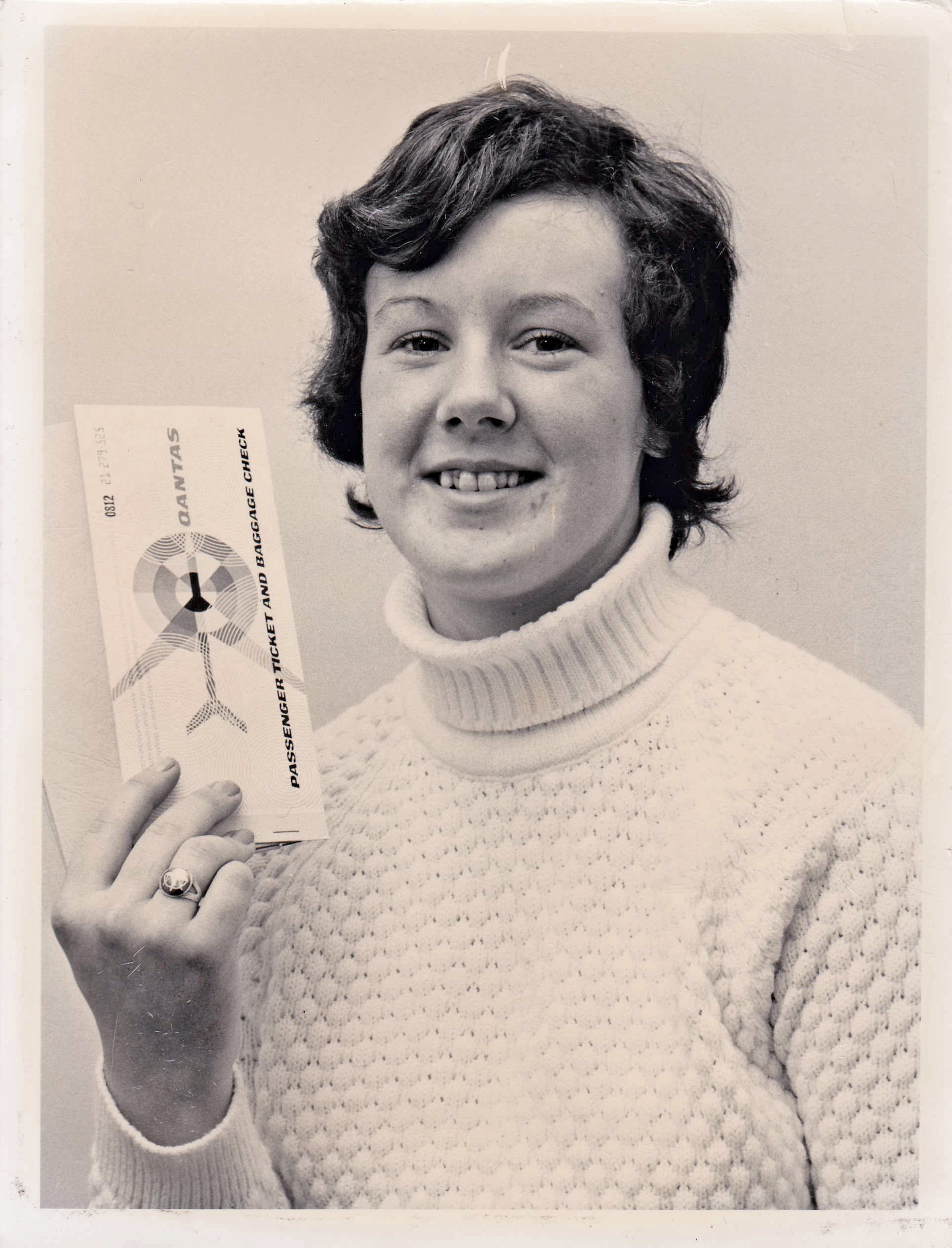

1970s engineer officer Marion Pettigrew, still finding the fit of her boiler suits a challenge after they had been through the wash. Images: Courtesy of Marion Sambridge

It is 1973 in Motherwell, Scotland, and a girl called Marion Pettigrew is looking at subject options for her O Grade exams.

She decides to tick a box to study technical drawing and metalwork rather than domestic science – the first girl at her school to do so.

Her spirited choice leads her to get to know the metalwork teachers, who hear how much she wants to travel. Mr Hunter has a relative in the Merchant Navy, so suggests that Marion gives this a try. It is the spark of a career which still stands out as unusual for a woman 50 years later.

Applications and interviews

Sending out 22 enquiry letters about Merchant Navy engineering cadetships in 1975, Marion had a feeling shipping companies wouldn't consider her if she gave her first name, 'so I just wrote my initial M. Sure enough, all the replies came back addressed to Mr Pettigrew! But I ended up with three interviews.'

For the first interview, at Ben Line, Marion was told to bring her father. 'The guy berated him for allowing me to consider this as a career, and went on and on about whether I'd be able to swing a 50lb hammer.'

The second interview was no better, but at P&O (which was then a cargo shipping company) everything was different. 'They gave me a proper interview like everyone else, which included modern techniques like psychometric tests.'

And so it was that Marion, aged 17, started her P&O engineer officer cadetship in September 1976 at Glasgow College of Nautical Studies.

Mixed experiences at college

The training for engineering cadets was a four-year course, with two college years, a year at sea and then back to college. Cadets were encouraged to join the Merchant Navy and Aviation Officers' Association (MNAOA) – a predecessor trade union of Nautilus International.

Marion was the only female engineer cadet out of 107 in her college year, and it wasn't easy at first. 'There were all these snotty young boys, the majority saying, "what are you doing here?". Thankfully, around November, some deck cadets came back from their sea phase, including one female who became a lifelong friend. With new friends who accepted me, I settled in and my studies improved.'

Stepping shore in size 4 boots

When the time came for Marion's sea phase, she flew out to Saudi Arabia to join the P&O gas carrier Garinda after a big effort to get equipped. 'It had been hard to find steel toe-capped boots in size 4 and my mum had needed to adjust my boiler suits to make them fit.'

Her presence onboard ship was not only a new experience for Marion, but also for P&O, for whom she was the first ever female engineer. Her shipmates weren't too sure what to make of her, but she remembers them as friendly and helpful.

Her other two vessel placements – on general cargo and container ships – also generally went well, and she decided to take a job with Overseas Containers Ltd (OCL) when she finished her cadetship.

A good company to work for

Marion served on container ships with OCL – later known as P&OCL – for the rest of her sea career. 'OCL was a decent company with modern ships and a good atmosphere onboard,' she explains. 'They made an effort to keep crew members together who knew each other, which made it easier to just geton with the job rather than people being surprised to see me.

'I only had one difficult chief engineer, who used to sing a nasty little song about me. Also, there was a captain who told OCL he didn't want a woman engineer onboard, but the company backed me, and he ended up sorting himself out.'

Translating sea experience into shore success

In September 1985, Marion decided to come ashore. Remaining with P&OCL, she took an office job selling secondhand containers, and her next move was to Tiphook Container Rental, where she set up an engineering department relatingto container repairs. She also worked in Tiphook's IT department as a user acceptance tester.

In 1992, Marion finally left maritime to establish herself as an independent software developer and business analyst – work that she still does.

Reflecting on the past

Now known as Marion Sambridge, and with a grown-up daughter, she looks back at her youth with a certain bemusement at her own boldness.

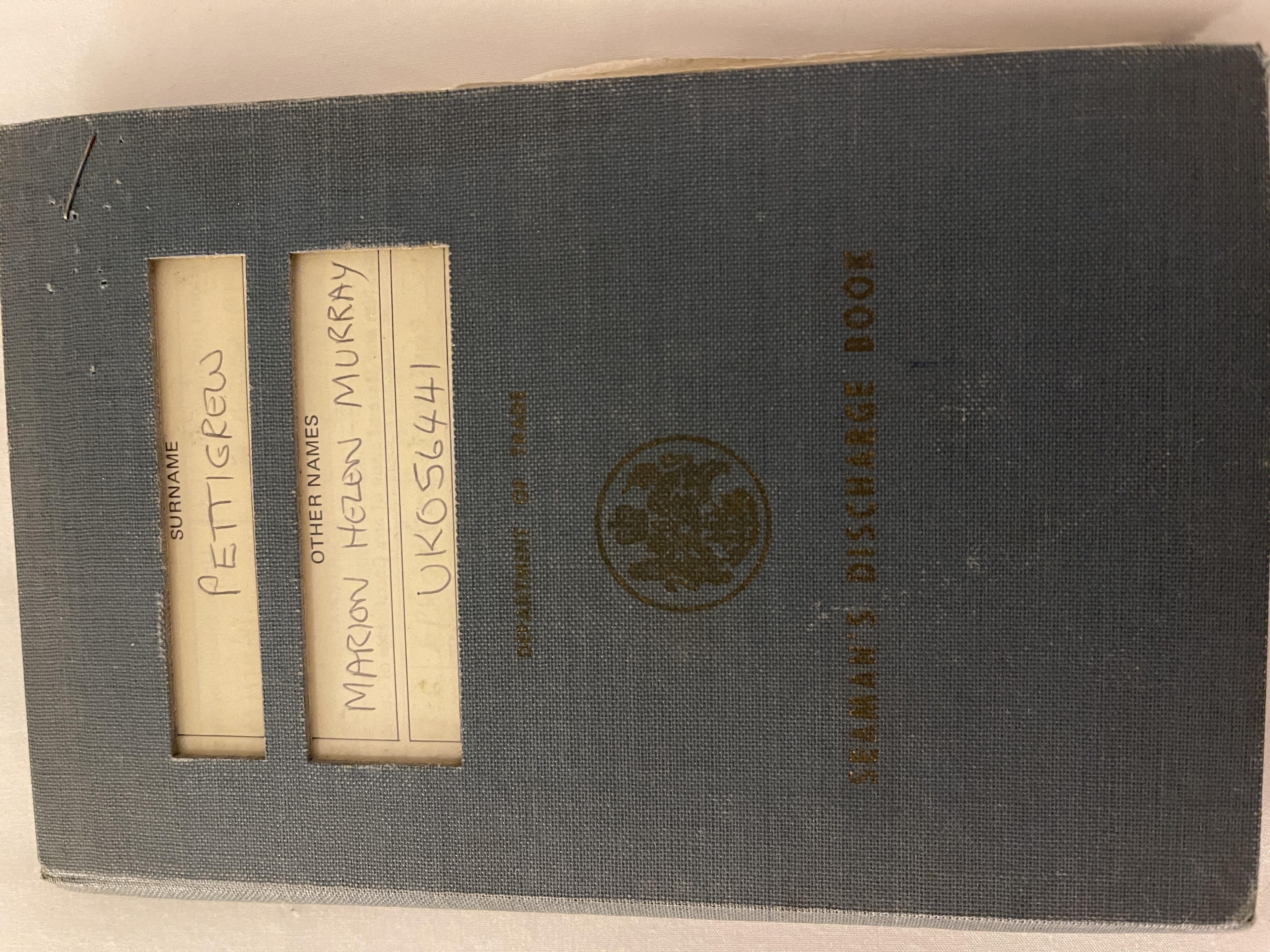

Marion Pettigrew's SeaMAN's discharge book.

'It's strange to think of myself as a pioneer,' she muses, 'because I didn't set out to do that; I was just very bloody-minded when it seemed like I might not be allowed to do something!'

Marion remembers her time at sea vividly.

'At its worst, it could be dirty, sweaty and lonely – and frightening in bad weather. There were a few difficult people, but I gave as good as I got and never felt unsafe.

'At the good times, it was the best time of my life. I went to amazing places, did interesting work and met the best people, many of whom are still good friends. I owe my career to the people at P&O and OCL and I am forever grateful to them.'

ROSE KING – RADIO OFFICER

Rose King is the only one of our three officer pioneers to stay at sea until she retired, and she's still a member of Nautilus. Sarah Robinson relates how books played a key role in a long maritime career

Life is often a game of chance, and Rose King's maritime career is a case in point.

Born in Britain, Rose spent the latter part of her childhood in South Africa, and on leaving school in Cape Town, she took a job in a department store.

'It was boring and I wanted a change,' she recalls, 'so when I saw a job advertised at the Union-Castle Line office next door, I decided to apply for that instead.'

This one spontaneous decision was how Rose ended up with a lifelong career in the shipping industry. Her first job involved booking cabins for passengers on Union-

Castle's ships, and later she moved to the company's accounts office in London.

From shore to sea

Rose was still keeping her career options open, and it was through another random happening that she ended up as a radio officer. Always an avid reader, she came across a maritime book in her local public library in which a shipmaster wrote very interestingly about his career at sea. 'There was advice at the end about how to do it yourself – so I thought that could be me.'

There was nothing in the book about careers at sea being only for boys, so that was encouraging, but it did say that deck and engineering cadetships usually started

between the ages of 16 and 18. As Rose was 21 by then, she noted that radio officer courses would take older students, and therefore decided that this would be her path.

'Then I wrote off to some colleges, got some replies and chose Lowestoft because the fees were fairly cheap and I'd been there before on holiday,' she says simply.

Unlike deck and engineer officer training, employer-sponsored cadetships were not available for radio officers, but Rose won an educational grant from the County Council of Hertfordshire, where she lived.

Good times in Lowestoft

The year was 1971 when Rose arrived at Lowestoft College on the east coast of England. It turned out that she was the first female student ever to join the radio officer course there, but Rose took that very much in her stride. 'I wasn't bothered, but the college must have told the BBC, because a crew from the local news programme Look East turned up to interview me. I was lodging at the YMCA at the time, and my friends and I all crowded into the TV room to see me!'

Rose found the male students on her course to be friendly, and the college had a good atmosphere, with students encouraged to take part in activities like putting on plays. It was also at college that Rose first joined the Radio and Electronic Officers' Union (REOU), a predecessor of Nautilus International.

A different way to be employed at sea

When she qualified after three years, her next step was not to apply for a job with a shipping company, but instead with a marine radio equipment manufacturer.

Radio officers like Rose would be trained in the equipment of Redifon, Marconi or International Marine Radio and then deployed on vessels which had that equipment onboard.

As the years went by and this system became less common, Rose was also sometimes employed directly by shipping companies, and sometimes by maritime job agencies. She found that she preferred fixed-term contract work, and never stayed long-term with an individual shipping company. Her career took her onto container vessels, survey, offshore, general cargo, tankers and even military corvettes.

From radio officer to ETO

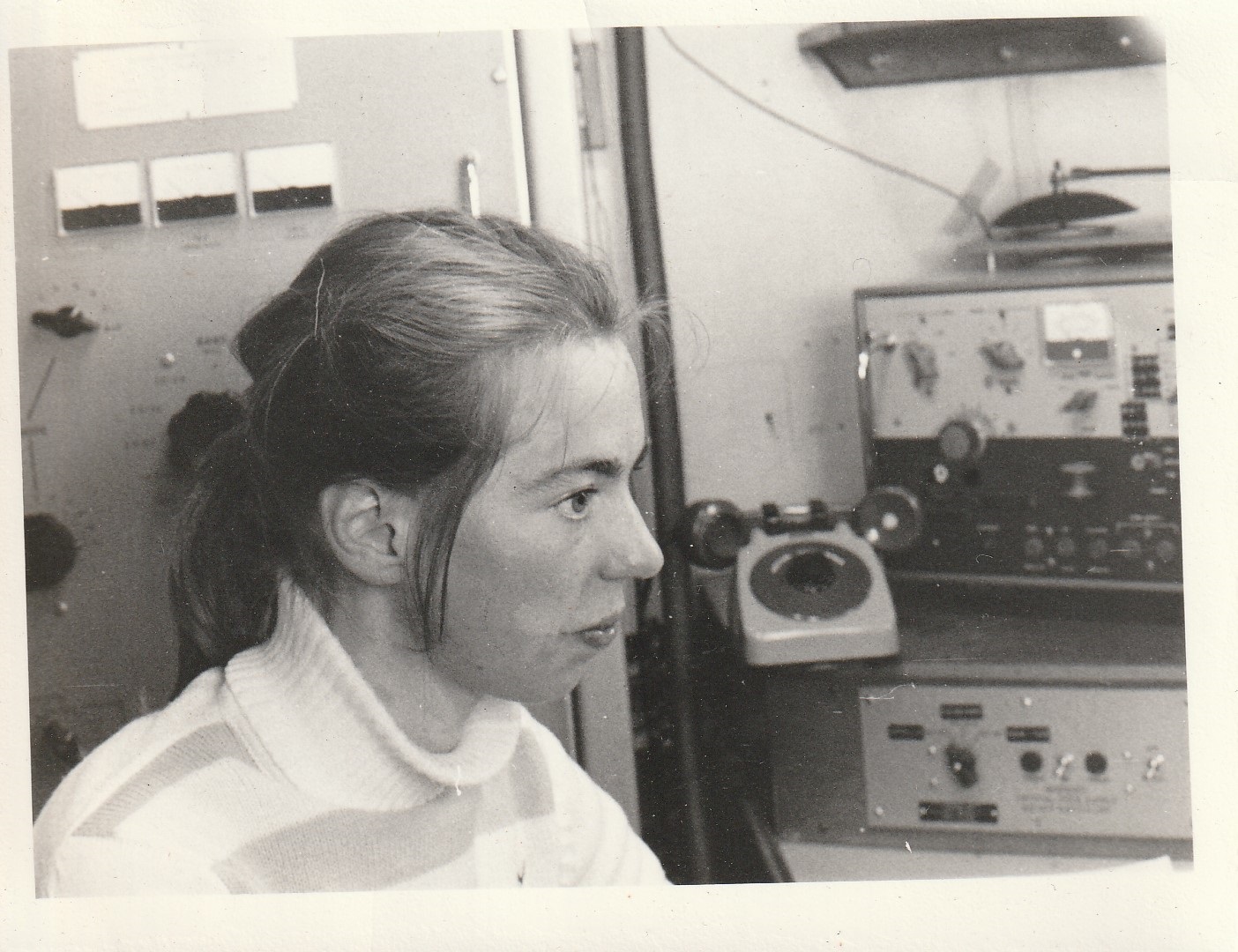

Through all these posts, Rose's own work was evolving. 'The radio officer job involved all the communications – first using Morse and radio telegraphy, all maintenance of the radio equipment and bridge electronic equipment including radar, direction finder, log and gyro. Then the job expanded to engine room electronics and equipment such as lifts.'

Rose King later in her career, when her role had evolved from radio officer into ETO

By the late 1980s, she could see that the role of radio officer was on the way out, and she undertook self-funded training at the University of Southampton to gain a City & Guilds qualification in marine electronics. She then sailed as an electro-technical officer (ETO) until her retirement in 2012.

Alone but not lonely

Throughout her career at sea, Rose was almost always the only woman in the crew. Luckily, this didn't ever bother her. 'Well, radio officers usually worked on their own, which I liked, and then I was in a small team as an ETO. The men were generally all right, but if they weren't, you'd just have to tell them where to get off.

'There was once a master who said to me "I'm as randy as a badger," and my reply was "Sorry, Captain. I have no idea as to the sexual habits of badgers," and then I scarpered. He gave me no more trouble after that.

'It wasn't a career for a quiet, shy person but it was fine for me. The main advice I'd give anyone is to make sure you bring enough to read!'

Tags

More articles

A trade union like no other: the full history of Nautilus International

Tugmaster Lorna Baird on sea blindness, ship-handling and volunteering

Nautilus caseworker in Tyne and Wear receives accolade for 'exceptional dedication' to maritime community

Gwen Rayner, the Nautilus Welfare Fund caseworker serving the Tyne and Wear area, has received the Lord Lewin Award for outstanding service to the community from the Shipwrecked Mariners' Society.