- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

There have been worrying indications in recent years of a global rise in the seafarer injury and death rates – with particular concern about suicides. But when leading maritime academics tried to assess the true scale of the problem, they found themselves hampered by poor record-keeping in the industry…

Seafarers appear to be suffering more work-related deaths and injuries than they were at the start of this century, according to a new study.

But the report, from Cardiff University's Seafarers International Research Centre (SIRC), warns that flag states are failing miserably to keep accurate data on the health and safety of their crews.

Seafaring, the report notes, is often cited as one of the most dangerous occupations. However, getting meaningful statistics to compare death rates in shipping with other industries is 'plagued with difficulties'.

SIRC has been seeking to tackle the problem through a long-term initiative to persuade flag states to collect and share accident and injury data. After what it describes as 'lengthy negotiations' with the top 30 flag states, it managed to secure agreements with seven maritime administrations to access their information.

Even then, SIRC experienced significant problems with the 'erratic provision of data' it received from the seven administrations. In what it described as 'one very good year', six of the seven provided data, and in 11 of the 17 years studied it received data from five – although these were not consistently the same five administrations. In four years, SIRC received figures from four administrations, and in one year only three provided statistics.

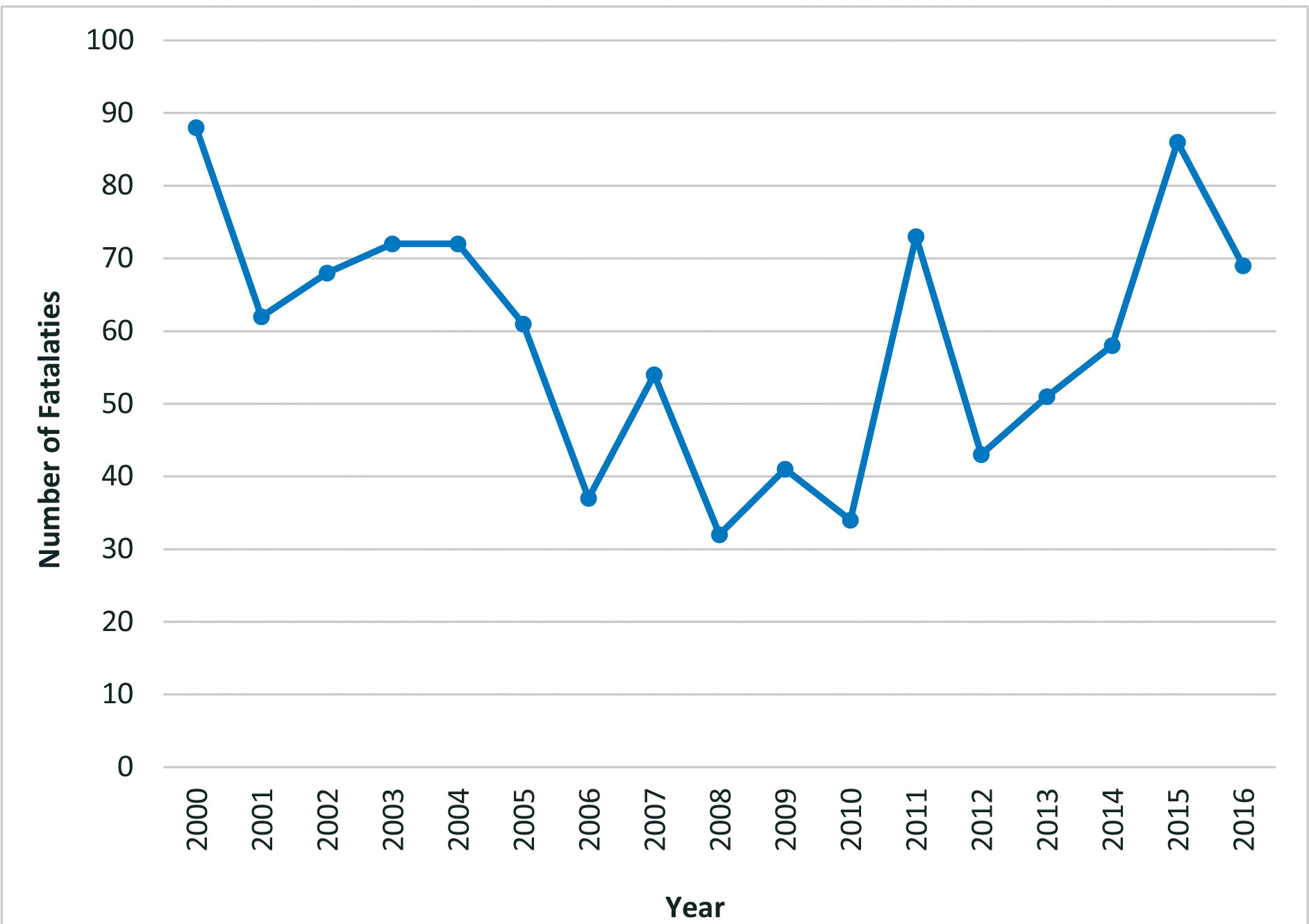

Despite these challenges, researchers were able to determine that there had been a decline in the rate of seafarer fatalities between 2000 and 2008. However, they noted, the available statistics show a 'broadly rising trend' from 2008 to 2016 – strongest from 2011 onwards.

With the shipping industry increasingly concentrating on the wellbeing of crew, the study sought to identify accurate figures on suicide rates amongst seafarers. However, SIRC said this was not an easy task.

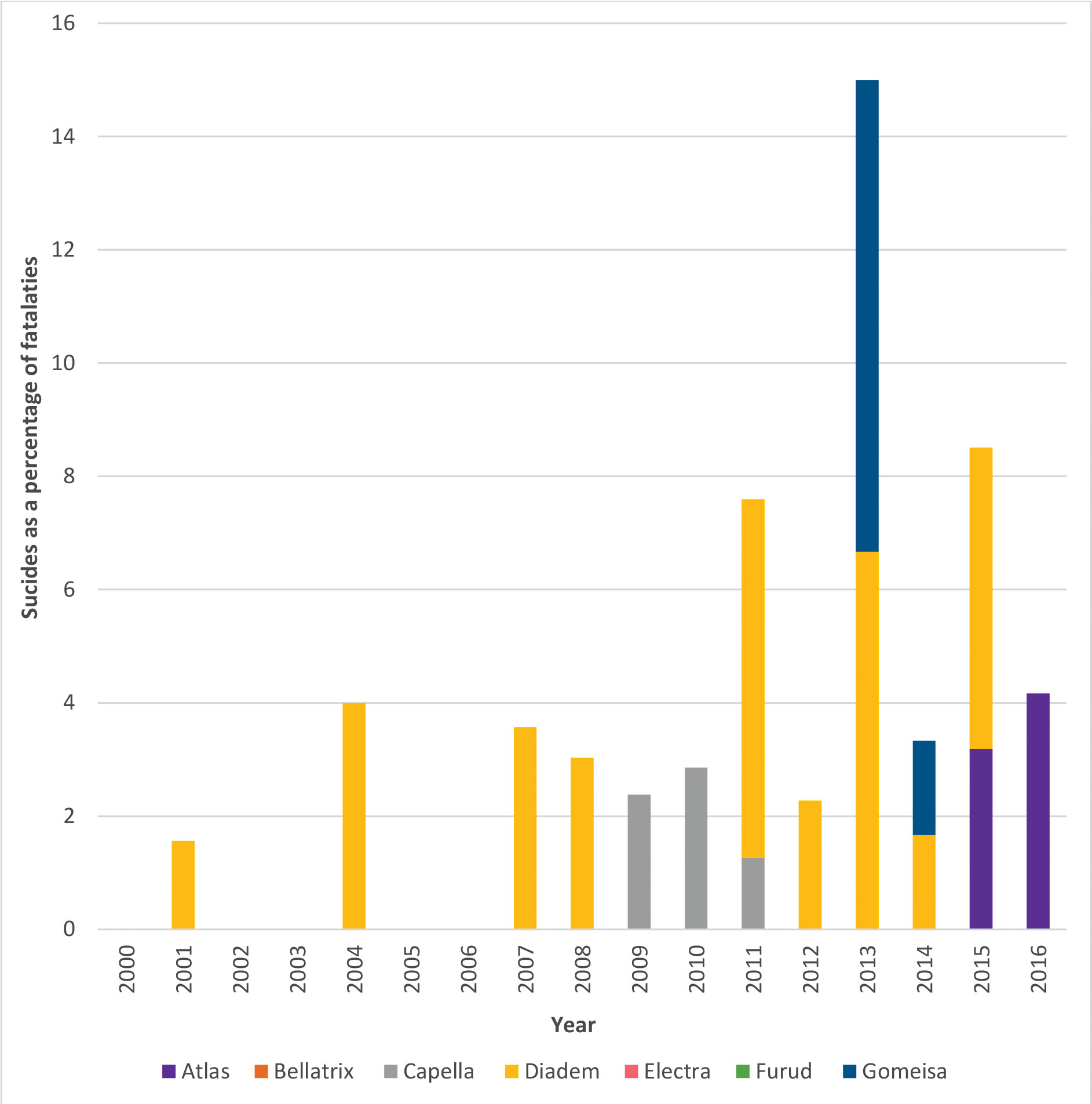

When reported suicides are compared with the overall level of deaths at work from accidents and natural causes, the study suggests that suicides constituted a relatively small proportion of total fatalities in the period between 2000 and 2016. Of a total of 1,039 fatalities over the 17 years covered by the study, 3.7% (38 cases) were identified as suicides. 'Most of these were identified in the period 2007-2016,' the report adds. 'Only four cases of suicide were recorded in the period 2000-2006 (inclusive): one in 2001 and three in 2004. This suggests that until 2007 suicides were generally not recorded in such a way as to be identifiable – they were simply categorised as "fatalities" without further details being provided.'

It is particularly disappointing that notwithstanding the attention which has been drawn to this problem, under-reporting of injuries appears to be a problem of increasing, rather than diminishing, magnitude

The researchers also identified serious problems with the reporting of injuries suffered by seafarers. Normally, they note, there is a pyramidal relationship between minor injuries, major injuries and fatalities in workplaces – with fatalities accounting for a very small percentage of total incidents (the peak of the pyramid) and minor injuries representing the majority of incidents (the base of the pyramid).

'In our data, fatalities (excluding suicides) constitute quite a significant proportion of incidents, averaging 7.1% of all incidents across all years,' the report notes. 'This is in itself suggestive of significant underreporting of injuries. However, under-reporting becomes even more evident when comparing the percentages of injuries as a proportion of all incidents recorded by each maritime administration.'

Data from one flag state indicated that fatalities constituted 87.3% of all incidents in the period, while at the other end of the scale – where 'the reporting and recording of injuries is far more conscientious' – two administrations reported that fatalities only constituted 3.5% and 3.3% of all incidents.

'As a result of the evidence of significant under-reporting of injuries and the very different practices observed by the contributing maritime administrations, we are unable to report any meaningful trends or figures concerning injuries in this period,' the report states.

'It is particularly disappointing that notwithstanding the attention which has been drawn to this problem, under-reporting of injuries appears to be a problem of increasing, rather than diminishing, magnitude,' it adds.

SIRC said the availability of information about seafarer safety has been a concern since its launch in 1995 – and things are little better now. 'As the world fleet has flagged out to "open" registers, the problem has been exacerbated, as open registers have been identified as particularly problematic with regard to the collection of data and the provision of access to it,' the report points out.

'Considered over a very long period of time, there is little doubt that the shipping industry is generally becoming safer,' it adds. 'However, the trends revealed by these data suggest that in relation to seafarer mortality, the industry remains exposed. Having seen a decline in the numbers of seafarer deaths reported in the first eight years of the period 2000-2016, the data indicate that seafarer fatalities have increased, and for (combined) administrations where we have data for the whole 17-year period there were more fatalities, in numeric terms, in 2016 than there were in 2000.

'In terms of suicide, the data paint a grim picture if taken at face value,' the report points out. 'However, despite the sharp increase in recorded suicides in the period 2009 onwards, the evidence strongly indicates that this reflects poor recording practices prior to 2009.

'There are also strong indications that within almost half of this small sample of maritime administrations, the recording of suicides is still not undertaken or is obscured via classification processes which merge suicides with fatalities,' it explains. 'In numeric terms, therefore, the picture for suicides is likely to be much worse than represented in these data whilst at the same time we are unable to conclude from the information provided that suicides amongst seafarers are increasing.'

SIRC says the lack of decent data means there is little meaningful value to be taken from the figures it gathered on seafarer injuries. To make a proper assessment of the risks associated with working at sea, the report argues that much more reliable information is required on the number of seafarers and more consistent ways of reporting and recording of deaths and injuries should be in place.

Only then, SIRC warns, will it be possible to gain an accurate insight into death, injury and suicide rates and a proper understanding of the health and safety challenges facing seafarers.

Main image: Eric Houri

Tags