- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

During the coronavirus pandemic, the true nature of the ship registration business and the predominant practice of registering vessels in flags of convenience has been starkly revealed, as they surrendered any semblance of upholding seafarers' rights or supporting crew denied repatriation, access to medical care or welfare support ashore. We must learn a lesson from this, says Nautilus general secretary Mark Dickinson. Never again can we allow the fundamental rights of seafarers to be swept aside by substandard ship registers and impotent flag states that corrode the governance of the shipping industry

The shipping industry’s chickens came home to roost this year with (allegedly) one sneeze in a wet market in Wuhan, China.

For decades, much of the industry has been operating in the shadows. Invisibility for many operators was the key: stay out of sight and they would be left alone, except when tax breaks and subsidies were on offer. Then they come out of the shadows.

Shipowners register vessels under flags of convenience (FOCs) for limited liability, light touch and flexible regulation, accessible politicians and low or no taxes.

When the pandemic hit, who did shipowners turn to? Did they hot foot it to Panama City, Monrovia or Majuro? No, when they are in trouble, they beat on the doors of their home country demanding bailouts, state subsidies and diplomatic interventions.

But the shipping industry’s obsession with secrecy and invisibility has left seafarers brutally exposed. Most of shipping is now registered in flag states known as flags of convenience. These were shown to be powerless when transportation hubs and port states locked down. With no one enforcing their rights under international law – including the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) – seafarers have been denied repatriation at the expiry of their contacts. They have been denied medical care ashore, even for non Covid-related illnesses such as strokes, broken bones, tumours and dental care. Deceased seafarers have been kept in the ship’s cold storage alongside food because port authorities refused to allow their bodies to be repatriated for burial.

The inconvenient truth about the global shipping industry and its response to Covid-19 was highlighted by Hugo de Stoop, head of tanker operator Euronav, who said: 'At the heart of the problem is the way we have built this industry in the past. We have tried to live in the shadows, tried to be discreet, tried to be forgotten. Nobody wanted to pay tax, nobody or be heavily regulated. We have chosen tiny jurisdictions like Panama, Bahamas, Marshall Islands.'

Post-FOCs

Never again can we allow international conventions setting out the fundamental rights of seafarers to be swept aside with such seeming impunity. We can blame the countries that locked out the industry and its seafarers, but that would be to miss the point.

The seafarers did not expect that the response of the leading flag states would be such an abject surrender or demonstration of their impotence. The seafarers were left brutally exposed and forced into staying at sea. This is unacceptable, tantamount to forced labour, and the reasons why this occurred need to be understood and corrected.

The institutions of global regulation are essentially robust. But they are not enough. They must be bolstered. We need to weed out the self-interested. A frank and open appraisal of the governance and structures of the shipping industry and the corrosive effect of flags of convenience is necessary now more than at any time in our recent history. In history we may have the answer. In 1986 under the auspices of the UNCTAD a convention that would have outlawed flags of convenience was adopted. It has however failed to gain enough ratifications to enter into force and languishes on a dusty shelf at the United Nations. Perhaps it is time to revisit this convention?

Whatever the answer is we need to start with the enforcement of a genuine link between flag and shipowner and ensure that flag states effectively exercise jurisdiction and control over their ships. It is a matter of life and death for the world’s seafarers.

National flag shipping has suffered greatly, firstly from the growth of FOCs, and then as traditional maritime countries fought back by deregulating – establishing ‘lighter touch’ international or second registers and ultimately deregulating their national flags. The spiral downwards and the resulting insanity are all on show, as evidenced by recent incidents involving the Panama-flagged Wakashio and Gulf Livestock I, and the Moldova-flagged Rhosus.

Race to the top

The working conditions of seafarers need to improve. International regulation must become a race to the top, not a continuation of the race to the bottom. This is both for the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) to address but needs the support of their member governments for substantive progress to be made. In the IMO the corrosive influence of the flag of convenience states needs to be addressed.

It is another inconvenient truth, but international conventions represent the minimum acceptable standards, and all too often the maximum that all IMO and ILO member states can accept.

That doesn't have to be the case. For example, building on the model of the IMO STCW Convention the MLC was conceived as a living document, a journey not a destination, capable of being amended to keep it up to date.

We need a genuine commitment from all parties to deliver continuous improvement in seafarers’ working conditions and support the race to the top for all international regulations. Only then will we have some sanity in the industry, improve health and safety and the protection of the environment to say nothing of enhancing the attractiveness of shipping as a career.

We need the IMO and ILO to address crewing levels, and by doing so call time on fatigue and the long hours culture which sees many seafarers working over 90 hours per week. The debate about technology and automation needs to be human-centred – not 'How do we replace seafarers?' but ‘How do we use technology to enhance their working and living conditions?’

National priorities

Nations and society need to relearn and understand the importance of shipping and seafarers to the global economy. The economic case is solid, and the UK and Netherlands are two examples showing that investing in your shipping industry is a win-win for the national economy and beyond.

The alternative, being reliant on others for all your shipping needs, is strategic suicide and must be avoided. Maritime resilience is crucial to any country that relies on shipping for imports and exports.

The UK and Dutch experience of laissez faire government policy saw national fleets shrink massively, and the numbers of seafarers being trained plummeted to almost nothing. Now we have Tonnage Tax systems and financial support for maritime training, plus social insurance and income tax benefits for employers and seafarers. These examples of state intervention are good, but such positive measures require constant attention – they can never be 'job done' they need to be kept fresh. It is crucial to ensure they continue to deliver in the national interest.

Direct intervention by governments is essential. Either by regulating the conditions upon which shipowners can enter the market (sometimes referred to as cabotage) or by providing fiscal support. These interventions are not mutually exclusive, but they must be strictly focused on goals in the national interest.

Fighting for fairness

Shipowners must ask themselves whether their governance, their flag and crew strategies are defendable set against the increasing desire of societies for sustainability, transparency, fairness, decency and for the environment to be protected.

Hiding in tax havens, avoiding scrutiny, supporting deregulatory approaches; none of this is aligned with the demands of today’s society and our young people.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria are now mainstream in investment decisions. Investment funds such as Fidelity and global shippers such as Unilever and Danone amongst many others are asking questions about the way the maritime industry is run. The crew change crisis has triggered this, but it was coming anyway, and there is a hugely significant conversation going on about the lack of transparency and accountability in this industry.

There are also international tax reforms coming into play which have the potential to shift shipowners away from registering their ships in offshore tax havens which represents an opportunity for bona fide flag states to rebuild.

Young people won’t work for companies that don’t meet their aspirations for sustainability. Increasingly I will wager, they won't vote for politicians who support the perpetuation of this broken system.

This year feels like a turning point in many ways, including a significant moment in history and a chance to reclaim lost ground. Let's not waste it.

The shipping industry's obsession with secrecy and invisibility has left seafarers brutally exposed

Broken link

Flags of convenience (FOCs) are by their very existence an abrogation of the requirements of Articles 91 (Nationality of Ships) and Article 94 (Duties of Flag States) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This convention requires a genuine link between the flag and the owner of the vessel, in order for the flag state to effectively exercise jurisdiction and control over ships flying its flag.

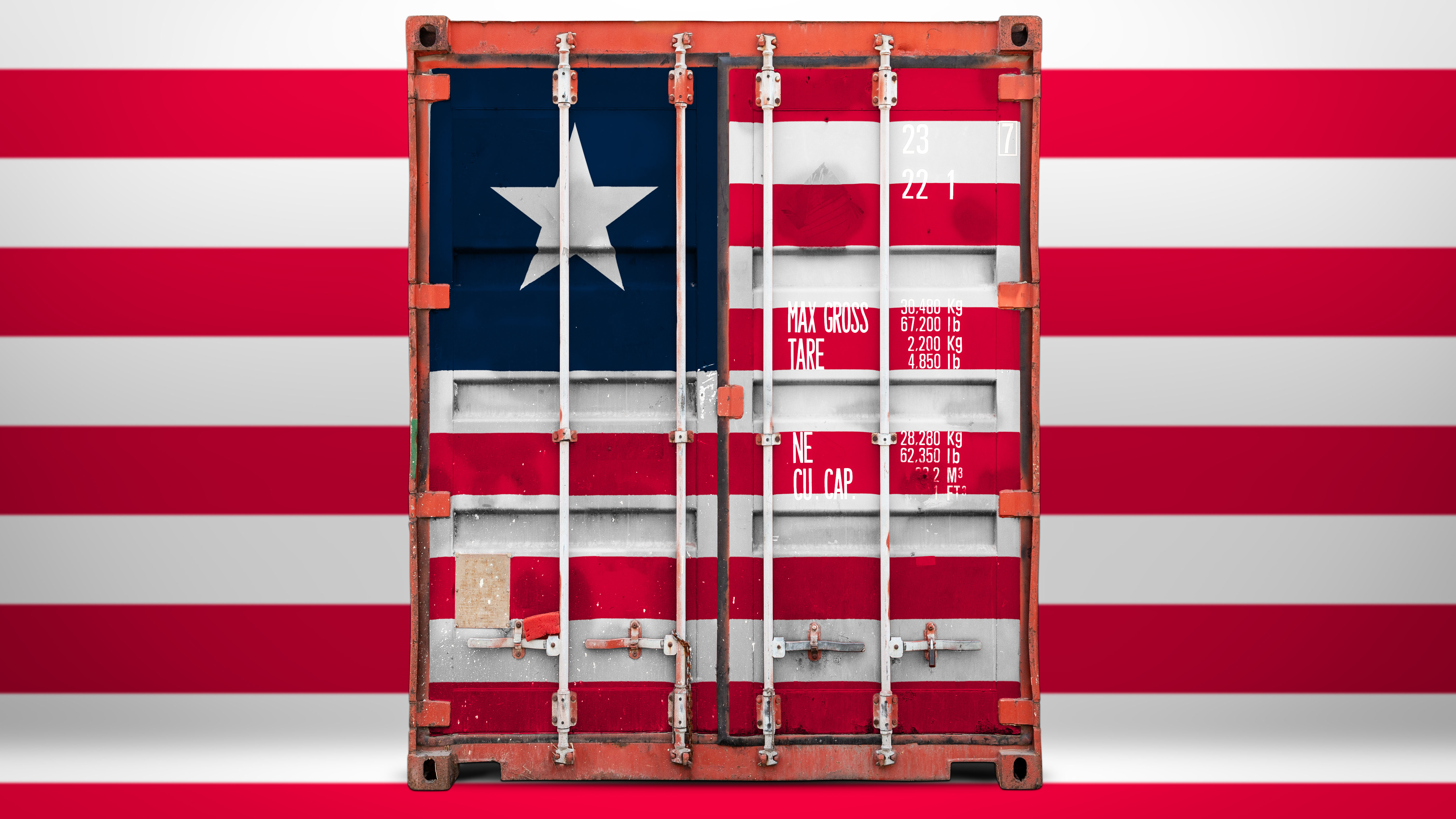

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the top three ship registers in 2020 are:

Panama – 333m DWT

Marshall Islands – 246m DWT

Liberia – 243m DWT

These three registers alone make up 40% of the world fleet and are all considered by the International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF) to be FOCs. Of the top 35 leading flags identified by UNCTAD over 950 million DWT is registered in just nine FOCs registers representing 48% of the total world fleet.

Campaigning for change

Since 1948, the International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF) has campaigned on behalf of all the major maritime trade unions to end the flags of convenience (FOC) system – its political objective being to require a genuine link in accordance with UNCLOS.

The ITF campaign has always had an industrial goal: imposing internationally agreed working conditions on the global shipping industry to protect seafarers and enhance their lives. Remarkably, with solidarity from the world's dockworker unions, that influence now extends to securing collective bargaining agreements on over 11,000 FOC vessels. It also influences minimum conditions on many national flag vessels too.

This campaign has also delivered the only example of an international forum – the International Bargaining Forum – where ship managers and shipowners represented on the Joint Negotiating Group meet and negotiate with the ITF to agree wages and working conditions codified in an International Framework Collective Bargaining Agreement.

Ultimately, the ITF's campaign work on behalf of the world's seafarers also delivered the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (as amended). This is often referred to as the 'Seafarers' bill of rights' and is a set of minimum standards covering all aspects of the employment of seafarers. It has been ratified by 97 countries representing 91% of the world fleet.

Tags