- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

There's been a lot of talk about a no-deal Brexit making life harder for seafarers with UK certificates, but what would this actually mean in practice? From Brussels, JUSTIN STARES looks at what the future could hold...

'No deal' would mean 'no favours', and that's not good news for seafarers who hold UK-issued certificates. As the European Commission has warned, the UK would under this scenario be treated as any other third country seeking permission for its seafarers to work on ships flagged within the European Union.

Existing UK certificates would remain valid until expiry, but, according to the Commission's hardline interpretation of the rules, certificate holders would not be able to switch jobs between ships registered in the various EU flag states.

While hard Brexit therefore looks grim both for British seafarers and thousands of others across the Commonwealth and elsewhere, all is not lost.

If the UK is forced to re-apply for EU recognition, the request is almost certain to be approved. British education and training standards already meet the European requirements, and there is no reason to expect objections when EU governments meet in the secretive Brussels committee that decides the fate of third country seafarers.

The only real question is: how long would re-recognition take? If it's a quick, seamless procedure, then UK certificate-holders could soon find themselves back in the European fold.

Officially, the assessment of the recognition application should take 18 months. This period is, however, in the Commission's own words, 'not realistic'. The team of inspectors at the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) already can't keep up with their ever-expanding rounds of 'visits' (the term 'inspection' is out of favour in today's Euro-sceptic world). The UK would have to wait in line for inspections that would in all probability turn out to be a mere formality.

EU rules on recognition applications, which are currently being redrawn in Brussels, set out two years as a more reasonable timeframe. Prior to applying, the UK would need to find an EU sponsor (again, not a problem: allies such as Malta would surely be willing to help). So, when you factor in a few months of mindless bureaucracy, three years seems achievable.

There is only really one 'but'. If there is any kind of problem with the Brussels inspection process, delays could soon add up. As other applicants have experienced, Brussels lives in its own time zone: GMT + ages.

Japan, which convinced Cyprus to act as its sponsor, applied for EU recognition in 2005. It took until November 2014 to push the paperwork through the Brussels machinery – that's nine years. According to the official version published at the time, the delay was due to Japan's reluctance to accept an EMSA inspection on sovereignty grounds. Despite the fact that the country's training system was largely up to scratch, 'lengthy discussions on the legal framework of the EU' were required.

In order to dissuade other countries from leaving the EU, could the Brussels executive, acting out of spite, deliberately hold up the UK’s recognition application?

In comparison, Bangladesh was processed quickly. Bangladesh secured three EU sponsors – Cyprus, Italy and Belgium – who collectively put in an application in July 2007. By December 2011, Bangladeshi seafarers had the Brussels green light to work on ships flagged within the EU. That's four and a half years.

For Fiji – sponsored by Germany – it took just over six years: from February 2011 to August 2017, plus a few more months until space could be found to publish the decision in the EU's official journal.

Technical glitches can be compounded by the discovery of substandard training institutes. If even one institute is not up to STCW standards, the others risk having to wait while remedial action is taken. Presumably, the UK's application would not suffer this fate.

Then there's the 'goodwill' factor. Or rather, the lack of it. The Commission in theory operates according to the rule of law. In practice, however, it is a political body with its own priorities. If one of those priorities were to make the UK's life as difficult as possible – in order to dissuade other countries from leaving the EU – could the Brussels executive, acting out of spite, deliberately hold up the UK's recognition application? That's anyone's guess, though mine is that it's possible.

On the plus side, once you're in, you're in. There have been very few cases of third country providers of seafarers who have seen their EU recognition removed: as few as two, according to old hands in Brussels. To have your recognition removed, you have to be engaged in the wholesale issuance of fraudulent certificates (as was the maritime authority in one former Soviet republic) or something similarly grave.

Not even the widespread discovery of substandard training centres was enough to see recognition removed from the Philippines, a country which was instead funnelled into a decade-long procedure involving multiple threats and numerous EMSA 'visits', all designed to encourage reform. These efforts have met with mixed success, judging by the fact that discussions regarding Filipino reforms are still ongoing in Brussels.

According to shipowners' sources, the Commission backed off from de-recognition because there are simply too many Filipinos working on EU-flagged vessels. These claims are difficult to assess, because statistics regarding seafarers – where they exist at all – are notoriously inaccurate. When Brussels was threatening the Philippines, anywhere between 5,000 and 60,000 jobs were said to be at risk.

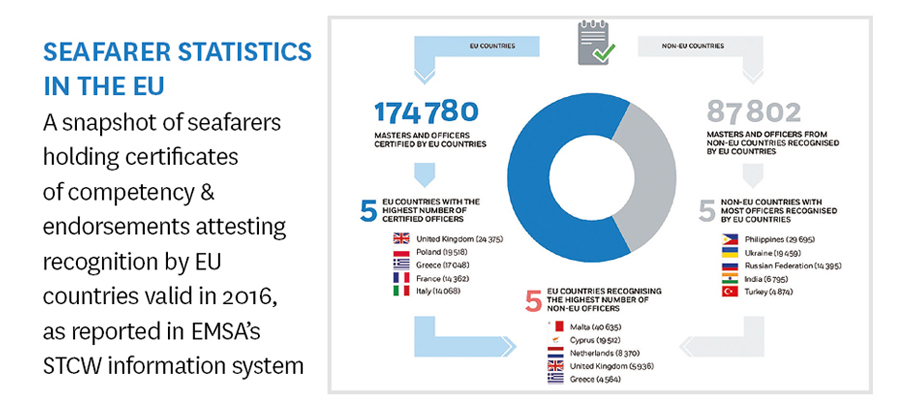

The same uncertainty applies to holders of UK certificates and their relative strength within the EU fleet. Figures compiled by EMSA in 2014 suggested there were around 220,000 EU seafarers and that the UK issued 28,865 certificates of competence that year, making the UK the largest issuer in the EU. These figures were, however, based on 'potential manpower' rather than the number of active seafarers, which was unknown.

The extent to which operations onboard EU-flagged ships would be interrupted if all UK certificate holders were effectively flung out is therefore a tricky question. The EU does, however, recognise around 50 providers of manpower from around the world. It is therefore a fair bet that the replacement of one certificate provider would not be an insurmountable task.

In conclusion, a no-deal Brexit would not necessarily be a disaster for UK certificate holders, though it would launch them on a journey into the unknown: all of which is unlikely to be reassuring for those currently considering revalidation.

- Justin Stares is editor of maritimewatch.eu

Tags