- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

Nautilus has been working on a series of initiatives to help members make the transition from one working environment to another. Now the science and engineering body IMarEST is following suit, using the results of a special survey to help guide marine engineers from sea to shore…

The prospect of coming ashore to progress one's career can be daunting to many working at sea, according to a survey of engineers who have made the transition. Conducted by the Institute of Marine Engineering, Science & Technology (IMarEST), the research showed that many had reported feeling apprehensive about making the move.

Those who found the transition relatively straightforward stressed the importance of studying for certain qualifications before leaving the sea. As one engineering superintendent explained, seagoing qualifications are acceptable for operational level posts but not the managerial roles that senior sea staff are aiming for: 'For that they need a degree and postgraduate qualifications.'

Many of those who struggled cited the practicalities of arranging interviews as a major frustration. It often proved hard for seafarers to schedule interviews whilst on leave and then persuade a potential employer to wait to meet until they returned from their next voyage.

One respondent warned that recruitment processes can take 'longer than your leave', whilst another was forced to take more drastic action by resigning from a current role to be ashore long enough to see the process through.

Another common difficulty was adjusting to working in an office environment. A typical comment was that, at sea, 'things have to be done and the results of them not happening are far more immediate and obvious. Ashore, people go home at 5pm. They are not living the job'.

There were other culture shocks: a need for greater diplomacy and patience, and adjusting to a less hierarchical management structure. Management onshore tends to be much flatter – but, as one respondent noted, this can actually complicate relationships: 'Sometimes the boundaries are unclear.' For the uninitiated, it can take time to learn and adapt to the slower pace and bureaucracy of this new environment.

Life at sea, away from friends and family, is often described as lonely. However, moving to shore means this loneliness can take on a new shape, particularly if the new role is away from home.

'It took time to come to terms with living in a new place and not knowing many people outside of the work environment,' said one technical superintendent. Nevertheless, on reflection, he added, it was worth persevering as 'in the end … it opened up many opportunities for career advancement and promotion'.

Technical skills and competence are only part of the story when it comes to stepping ashore. They must be accompanied by a mixture of 'soft skills' needed for effective people- and project-management, such as leadership, communication (verbal and report writing), negotiating and networking, and administration skills such as budgeting, finance, logistics and procurement. While the administration tasks done on ship are a sound foundation for developing the latter group, it can take longer to build the requisite people skills.

One chief engineer who came ashore to work as a class surveyor advised seafarers considering the transition to achieve as much as possible while at sea: 'That additional rank could turn out to be really crucial. The difference between serving as a chief engineer compared to second or third engineer is immense.'

The management and responsibility skills needed on land, he continued, generally come with higher ranks. A comprehensive understanding of the roles of class, P&I, flag and how they interact is imperative.

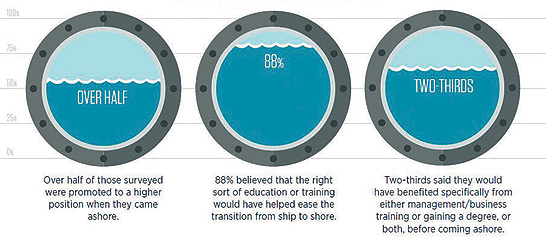

Several respondents said that secondments ashore during their seagoing careers would have (or had) helped prepare them to 'swallow the anchor'. An overwhelming 88% believed that the right sort of education or training would assist the transition. Two-thirds said they would have benefited from either management/ business training or gaining a higher education qualification such as a Bachelor's or Master's degree, or both.

'Leadership and management skills are essential to prove your worth to an employer and to complement the range of engineering skills that you have acquired at sea,' said one chief engineer who came ashore to take on a management role in gas processing.

Another chief engineer who had rarely felt outside his 'comfort zone' working on ship said his new role as a senior technical manager overseeing a wide range of projects demanded a totally different approach and attitude. 'Getting to grips with the interactions between all the different disciplines really made me appreciate the variety of the maritime world,' he commented.

The IMarEST has developed a qualification in Sustainable Maritime Operations to answer precisely this type of need. The distance learning programme can be studied whilst at sea, leading to either a post-graduate qualification or a BSc/MSc degree.

'Upskilling whilst at sea allows seafarers to stay at sea longer whilst still helping them move up the career ladder. Those who don't feel the urge to come ashore are not forced to do so before they really want to,' says IMarEST chief executive David Loosley.

Over half (56%) of those surveyed were promoted to a higher position when they came ashore. However, some saw a salary drop, which was often attributed either to a lack of formal qualifications or else a difficulty in communicating the relevance of their skills. As one respondent more plainly put it: a person working onboard is always considered a fresher when moving ashore.

Many of the seafarers surveyed reached the conclusion their skills were not properly recognised or valued by their shore-based colleagues. 'I was seen as a jack-of-all-trades and insufficiently specialised rather than a flexible employee with broad engineering experience who could work independently,' was a typical response.

A common predicament was explaining how skills gained at sea would carry over to roles on land. As one respondent pointed out, the diversity of skills in the maritime environment is largely unrecognised: 'I had to stop describing my experience for positions using maritime roles, instead everything needs to be communicated in terms of transferable skills.'

Another added that this was compounded by the fact that some skills acquired at sea don't translate readily to a commercial, shore-based setting.

One seafarer, who was eventually appointed as a senior lecturer at a maritime academy, confessed that his post-nominals – CEng MIMarEST, denoting Chartered Engineer and Member of the IMarEST – were his main entry route to employment ashore. Apparently few recruiters could relate to his marine qualifications and experience. 'I wholeheartedly believe that “CEng” was my passport to most of the interviews I attended – more so than the years of maritime experience in a senior position,' he added.

Mr Loosley says such experiences show the value of gaining Chartered, Registered/Incorporated or Technician status. 'That functions as a simple indicator of professional excellence, especially in those without formal academic qualifications,' he stresses. 'The opportunity for seafarers to gain professional registration is one that should be taken by all those setting their sights on a promotion.'

Management onshore tends to be much flatter – but, as one respondent noted, this can actually complicate relationships: ‘Sometimes the boundaries are unclear'

Tags